Screen Load Performance: How Fast a Screen Becomes Usable

- Aditya Choubey

- 4 days ago

- 8 min read

Table of Contents

Startup performance creates the first impression. Runtime smoothness determines how the app feels once it’s open. But there’s a third moment that often decides whether users continue or leave: how quickly a screen becomes usable.

An app can launch instantly and scroll smoothly, yet still feel frustrating if every screen takes too long to show meaningful content. Users don’t think about API latency, database queries, or response times. They care about one simple question: how long until I can actually do something?

That moment when a screen stops feeling empty and starts feeling useful - defines perceived speed more than any backend metric.

To understand why, it helps to think about a familiar real-world experience.

The Restaurant Analogy

Imagine you sit down at a restaurant and place your order.

The waiter takes it to the kitchen. You know the food is being prepared, but nothing is on the table yet. No water, no bread, no appetizer - just an empty surface and the feeling that you’re waiting.

Five minutes pass. Then ten.

Even if the kitchen is working efficiently, the experience already feels slow. There’s no signal of progress, no sense that anything is happening. The empty table creates doubt.

Now imagine a different scenario.

You sit down and place your order. Within a minute, the waiter brings water. A moment later, some bread arrives. Then a small appetizer. The main course still takes the same amount of time as before, but the experience feels completely different.

You’re not staring at an empty table anymore. You’re engaged. You can start eating, tasting, interacting with the meal. The wait feels shorter, even if the kitchen speed hasn’t changed.

This is exactly how screen loading works in mobile apps.

A blank screen with a spinner is like an empty table. Even if the data arrives quickly, the experience still feels slow because the user has nothing to interact with. But a screen that shows structure, placeholders, or partial content feels faster, even if the full data takes longer to arrive.

Perceived speed is not about how fast the kitchen works.It’s about what reaches the table first.

What Users Actually Wait For

When users open a screen, they are not waiting for your API, your database, or your server. They are waiting for something useful to appear. From their perspective, there are two moments that define the experience.

The moment meaningful content appears

The moment the screen becomes interactive

These are commonly described using two metrics: First Meaningful Paint (FMP) and Time to Interactive (TTI). These are not just engineering metrics. They describe how the interface feels during loading.

First Meaningful Paint vs Time to Interactive

First Meaningful Paint is the moment when the first useful content appears. This could be a product card, a message preview, a profile header, or a list of items. It doesn’t need to be the entire screen - just something that signals progress.

In the restaurant analogy, FMP is when the bread or appetizer arrives. The meal isn’t complete, but the experience has started. The user stops feeling uncertain.

In web performance, this idea has evolved into metrics like Largest Contentful Paint (LCP), but the underlying concept remains the same across platforms: how quickly the user sees something meaningful.

Time to Interactive, on the other hand, is the moment when the screen becomes fully usable. The user can tap buttons, scroll, enter text, or complete actions. In the restaurant analogy, this is when the main dish arrives.

FMP builds confidence. TTI enables action.

In modern web performance, TTI is often complemented by metrics like Total Blocking Time (TBT) or Interaction to Next Paint (INP), which focus on responsiveness. In mobile apps, however, the practical question remains the same: how long until the screen is usable?

Why Fast APIs Still Feel Slow

Many teams focus heavily on backend performance and assume that faster APIs automatically lead to faster experiences. In practice, users never see your API. They only see the screen.

Consider a typical scenario:

Step | System Perspective | User Perspective |

API responds in 300 ms | Fast backend | Blank screen |

UI waits for multiple requests | Logical sequence | Still waiting |

Data parsing on main thread | Processing | No visible change |

UI renders everything at once | Complete screen | Finally appears |

From the user’s perspective, the experience was slow, even though the backend was fast. The system was working, but the user had no evidence of it.

What Actually Slows Down Screen Load

Screen load issues rarely come from a single major problem. They usually result from several small design decisions that accumulate into noticeable delay.

Sequential API calls are one of the most common causes. Instead of requesting data in parallel, the app waits for one response before starting the next. This creates unnecessary idle time.

Large payloads also contribute to slow loads. When screens request more data than they need, network transfer takes longer, parsing becomes heavier, and rendering is delayed. Often, the UI only uses a small portion of what the API returns.

Heavy screen initialization is another frequent issue. Some screens initialize multiple services, load large assets, or perform complex calculations before rendering anything. All of this work happens before the user sees a single piece of content.

Blocking logic before the first render is especially harmful. Some apps fetch all data, build the entire UI, and only then display the screen. This creates long inactive states where nothing appears to be happening.

Finally, the absence of progressive loading makes everything worse. If the screen only renders after everything is ready, users see nothing during the wait. That absence of feedback creates the perception of slowness.

Metrics That Define Screen Load Performance

To evaluate screen load performance, a few metrics provide the clearest picture.

Metric | What it Measures | Why it Matters |

FMP | First meaningful content appears | Builds user confidence |

TTI | Screen becomes usable | Enables interaction |

Screen load duration | Total time to usable screen | Overall experience |

API response time | Backend speed | Diagnoses server issues |

P95 load time | Slowest 5% of sessions | Reveals real-world problems |

On mobile, FMP can also be affected by startup state. Cold starts often delay FMP compared to warm or hot starts, especially on lower-end devices.

Measuring Screen Load in Real Apps

Local profiling tools are useful during development, but they only show performance on a developer’s device. Real users operate under different conditions - slower networks, older hardware, and background processes.

On Android, developers typically use the Android Studio Network Profiler and Layout Inspector to analyze request timing and rendering delays. On iOS, Xcode Instruments helps identify slow requests and main-thread bottlenecks. In Flutter, DevTools exposes network activity, frame timing, and screen build duration.

Production tools such as Firebase Performance Monitoring provide real-user data,

including:

Screen load traces

Network request timing

Device-specific performance patterns

This helps teams detect slow screens, compare device performance, and track regressions after releases.

How to Actually Improve Screen Load Performance

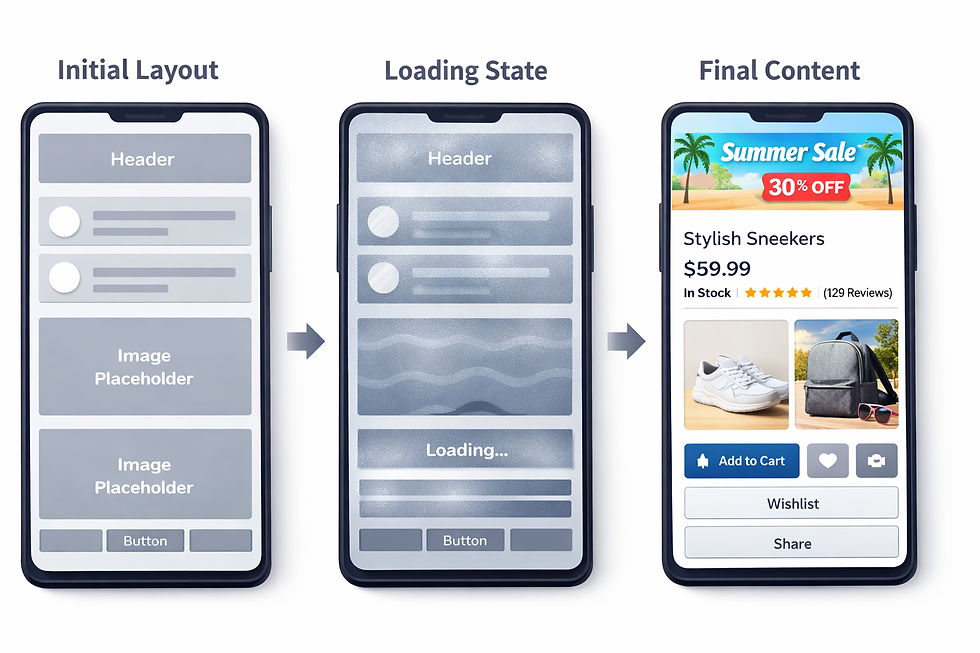

Most slow screens share one pattern: they try to do everything before showing anything. The fix is to show structure early and complete the rest progressively.

Render the UI before data arrives

Instead of waiting for data, render the layout immediately and fill in the content as it becomes available.

For example, a product screen can show its structure instantly while loading actual product data in the background. When the data arrives, the placeholders are replaced.

This simple shift removes the blank state entirely.

Replace spinners with skeleton screens

Spinners communicate waiting. Skeleton screens communicate progress.

A spinner tells the user nothing is ready. A skeleton shows where content will appear, reducing uncertainty and improving perceived speed.

Load critical data first

Not all data is equally important. Some elements are essential for usability, while others are secondary.

Critical Data | Secondary Data |

Product name | Reviews |

Price | Recommendations |

Primary image | Similar items |

If everything loads together, the screen stays blank longer than necessary. Loading critical data first allows the interface to become usable earlier.

Parallelize independent requests

Sequential API calls waste time. If two requests don’t depend on each other, they should run in parallel. This reduces idle time and shortens overall load duration.

Cache data for repeat visits

If a user visits a screen multiple times, the app shouldn’t fetch everything from the network each time. Cached data can be displayed instantly, while fresh data loads in the background.

This creates the illusion of instant loading.

Avoid blocking work before first render

Some screens perform heavy tasks before showing anything:

JSON parsing

Image decoding

Database reads

Complex calculations

If these run on the main thread, the interface remains inactive. Moving heavy work to background threads allows the first frame to appear quickly.

The first frame should appear as soon as possible.Everything else can happen afterward.

A Practical Loading Strategy

A simple mental model for building fast-feeling screens:

Render the screen structure immediately.

Load critical data first.

Show placeholders for secondary content.

Fetch secondary data in parallel.

Replace placeholders progressively.

This mirrors the restaurant experience:

Table appears instantly

Water arrives first

Bread follows

Main course comes later

The kitchen time may be the same, but the experience feels much faster.

Network Optimization Still Matters

While perception drives user experience, network efficiency still affects real load time.

Key strategies include:

Batching related requests

Reducing payload size

Using compression

Caching frequently used data

Running independent requests in parallel

Paginating large datasets

These improvements reduce both actual and perceived loading time.

Why Screen Load Performance Affects Business Outcomes

Users rarely abandon apps because the API was 200 milliseconds slower. They leave because the screen feels inactive or uncertain.

Slow screen loads lead to:

Shorter sessions

Lower task completion

Reduced conversion

Worse app ratings

Higher uninstall rates

Industry studies consistently show that faster content visibility improves engagement. Experiences that show meaningful content in under two seconds tend to see significantly lower bounce rates.

Perceived speed directly shapes user behavior.

Key Takeaways

Screen load defines perceived speed more than backend latency. Users care about when content appears and when the screen becomes usable.

First Meaningful Paint builds confidence. Time to Interactive enables action. Progressive rendering reduces uncertainty, while blank screens create doubt.

A fast startup and smooth scrolling are not enough. If screens take too long to become usable, the app will still feel slow—and users will behave accordingly.

FAQs

What is screen load performance in a mobile app?

Screen load performance refers to how quickly a screen becomes usable after navigation. It focuses on when meaningful content appears and when the user can interact, not just how fast the API responds.

What is the difference between FMP and TTI?

First Meaningful Paint (FMP) is when the first useful content appears on the screen. Time to Interactive (TTI) is when the screen becomes fully usable and responsive to user input.

Why does my app feel slow even when APIs are fast?

Apps often feel slow because the UI waits for multiple requests, processes large payloads, or builds the entire screen before rendering. Users judge speed by visible progress, not backend response times.

How can I make screens feel faster without changing the backend?

You can improve perceived performance by rendering UI structure early, using skeleton screens, loading critical data first, caching responses, and progressively loading secondary content.

What metrics should I track for screen load performance?

The most important metrics include:

First Meaningful Paint (FMP)

Time to Interactive (TTI)

Screen load duration

API response time

P95 screen load time

Comments